A Venezuelan Big Brother

A recent transparency report by one of the top telecom companies in Venezuela confirmed what many had long feared: state surveillance has reached a massive scale.

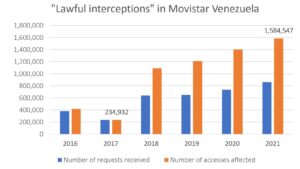

The Telefónica (Movistar Venezuela’s parent company) report revealed that more than 1.5 million Movistar phone lines were affected by interceptions of communications in 2021. According to the most recent figures from the National Telecommunications Commission (CONATEL), this represents almost 20 percent of all Movistar users in Venezuela.

Unlike internet censorship and website blocking, state surveillance is much more complicated to identify, especially in contexts with no rule of law, separation of powers, or institutional transparency. For many years, it was assumed that the Venezuelan regime was spying on persons of interest like journalists, politicians, human rights defenders, and more. But even some of the regime’s most critical opponents, including myself — a digital rights advocate who has provided digital security training to journalists and activists in Venezuela and other Latin American and Caribbean countries — were shocked to discover the actual scale of surveillance on civil society in Venezuela.

In 2020, the former director of the Venezuelan national intelligence service (SEBIN), Cristopher Figuera, acknowledged that the country’s telecommunications companies cooperate with the state to provide information on the activity of their users, spy on their private communications, and even collaborate with the execution of cyberattacks aimed at taking control of their accounts on digital platforms. Some of these allegations were corroborated in the detailed findings of the United Nations Human Rights Council’s independent fact finding mission on Venezuela.

Although Figuera noted in an interview with Código 58 that these practices were used against political opponents or persons of interest, the Telefónica report suggests a much larger scale operation than targeted surveillance.

The Telefónica report details both the number of requests received for interceptions of communications and traffic data in real time and the number of accesses (meaning phone lines) affected, noting a significant increase in both figures between 2017 and 2021. But it also includes information about metadata access requests, which can also reveal a lot of information about users and their actions, such as the source and destination of a specific communication; communication dates, times, and duration; the location of the user’s device; and more.

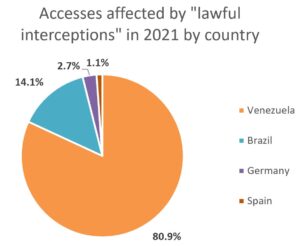

To provide context as to why the revelations about Venezuela in Telefónica’s report are so shocking, the graph below shows the proportion of accesses affected by “lawful interception” in 2021 by country. In this way, it becomes clear that the country’s figure is four times larger than that of the other 11 countries combined. In fact, Venezuela accounts for nearly 81 percent of accesses intercepted by Telefónica across all its countries in 2021.

While this is extremely alarming, it’s only the tip of the iceberg. Movistar serves less than 50 percent of the total mobile telephony users in Venezuela, while the other half is divided practically equally between Digitel and the state company Movilnet.

Movistar’s parent company, Spain-based Telefónica, stresses its human rights due diligence, highlighting in the report that it has received positive evaluations in assessments such as the 2020 Ranking Digital Rights Corporate Accountability Index and the Global Network Initiative’s independent evaluation process. Recognizing the challenges that arise from operating in a country like Venezuela, the company explained they must prioritize compliance with current legislation in order to maintain connectivity in the country and ensure the well-being of its employees.

Unlike Movistar, Movilnet isn’t accountable to any European company but answers only to the interests of the Venezuelan state and, therefore, to those who hold power in the country. When it comes to blocking access to websites and digital platforms, CANTV (another state-owned telecommunications company) is much more arbitrary and radical than Movistar. If the same thing happens with communications interceptions, Movilnet’s situation could be even more alarming than Movistar’s. But for now, much remains unknown.

Article 48 of the Venezuelan Constitution establishes the secrecy and inviolability of private communications in all forms. Likewise, it also establishes that they may not be interfered with except by order of a competent court. However, Telefónica’s transparency report includes as “competent authorities” not only prosecutors and police agencies, but also a public university dedicated to police training.

In addition to the telecom companies’ cooperation, there are other indications that Venezuela is surveilling its citizens on a massive scale. In 2020, the FADe Project also revealed that the largest number of potential IMSI Catchers were found in Caracas, more than in Mexico City, Bogotá, Santiago de Chile, or La Paz. An IMSI Catcher is a device that pretends to be a cell tower to carry out surveillance actions on citizens’ mobile phones.

But Venezuela is far from being the only country taking advantage of digital surveillance tools. Digital authoritarianism is also a growing trend in other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. In Cuba, for example, since at least 2016, text messages containing keywords such as “freedom” or “human rights” have been filtered and, during the national demonstrations and internet shutdowns of 2021, the list also included words like “VPN” or “Psiphon.” In El Salvador, journalists and activists were infected with Pegasus spyware, which is only sold to governments. And new laws and bills have also been promoted to regulate the content that citizens publish on digital platforms, promoting self-censorship in countries such as Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua.

Looking forward and fighting back

Members of at-risk organizations such as journalists, human rights defenders, and social and political activists must take measures to protect the security and privacy of their communications, such as:

- Avoid using phone calls and text messages to communicate sensitive issues. Instead, it’s recommended to use instant messaging apps that have end-to-end encryption such as Signal or even WhatsApp. These services also allow voice and video calls with end-to-end encryption.

- Set up two-factor authentication methods that don’t involve text messages (since these can be easily intercepted by state agencies with the help of telcos), such as physical security keys or apps like Authy across social media or email accounts, and instant messaging apps when available.

Although there isn’t much that can be done to stop the interception of communications through telecommunications companies, especially in authoritarian contexts, it’s possible to increase the pressure on these companies to demand transparency about these violations of privacy. It’s also necessary to increase awareness of this issue among local and international civil society. Cross-border advocacy will be critical in pushing for more transparency around state surveillance in Venezuela and other countries that employ these tactics against their citizens.

About the author:

David Aragort is a digital rights advocate and researcher working at the intersection of technology, democracy, and human rights with a special focus on the Internet, freedom of expression, and digital rights. He is also a fellow of the Open Internet for Democracy Initiative and part of the alumni network of the Internet Society and the Alliance of Democracies.

A recent transparency report by one of the top telecom companies in Venezuela confirmed what many had long feared: state surveillance has reached a massive scale.

— NEDemocracy (@NEDemocracy) September 20, 2022

Read @CIMA_Media's latest report from @DavidAragort: